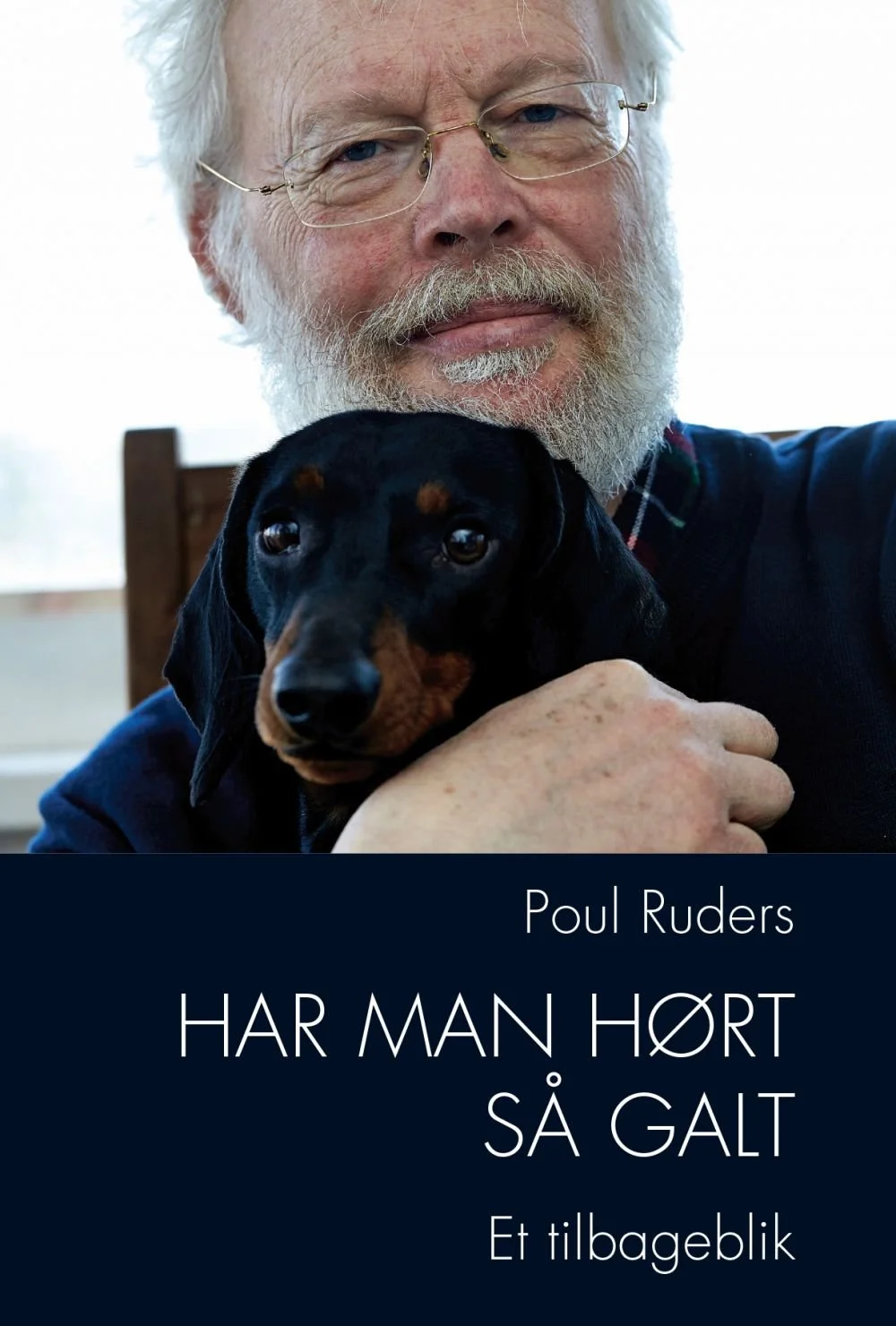

Would You Believe It: A Look Back (2000)

"Would you believe it - a look back is a translation from the original Danish of my short autobiography Har man hørt så galt - et tilbageblik, published in 2019 by the independent Danish publishing house Kahrius.

The book, which was launched as part of various activities in connection with my 70th birthday, is a personal "fact sheet", a frank and unpretentious walk through my life, from when I was born in 1949 up to the composition of my opera The Thirteenth Child in 2018".

Cover photo: Lars Skaaning

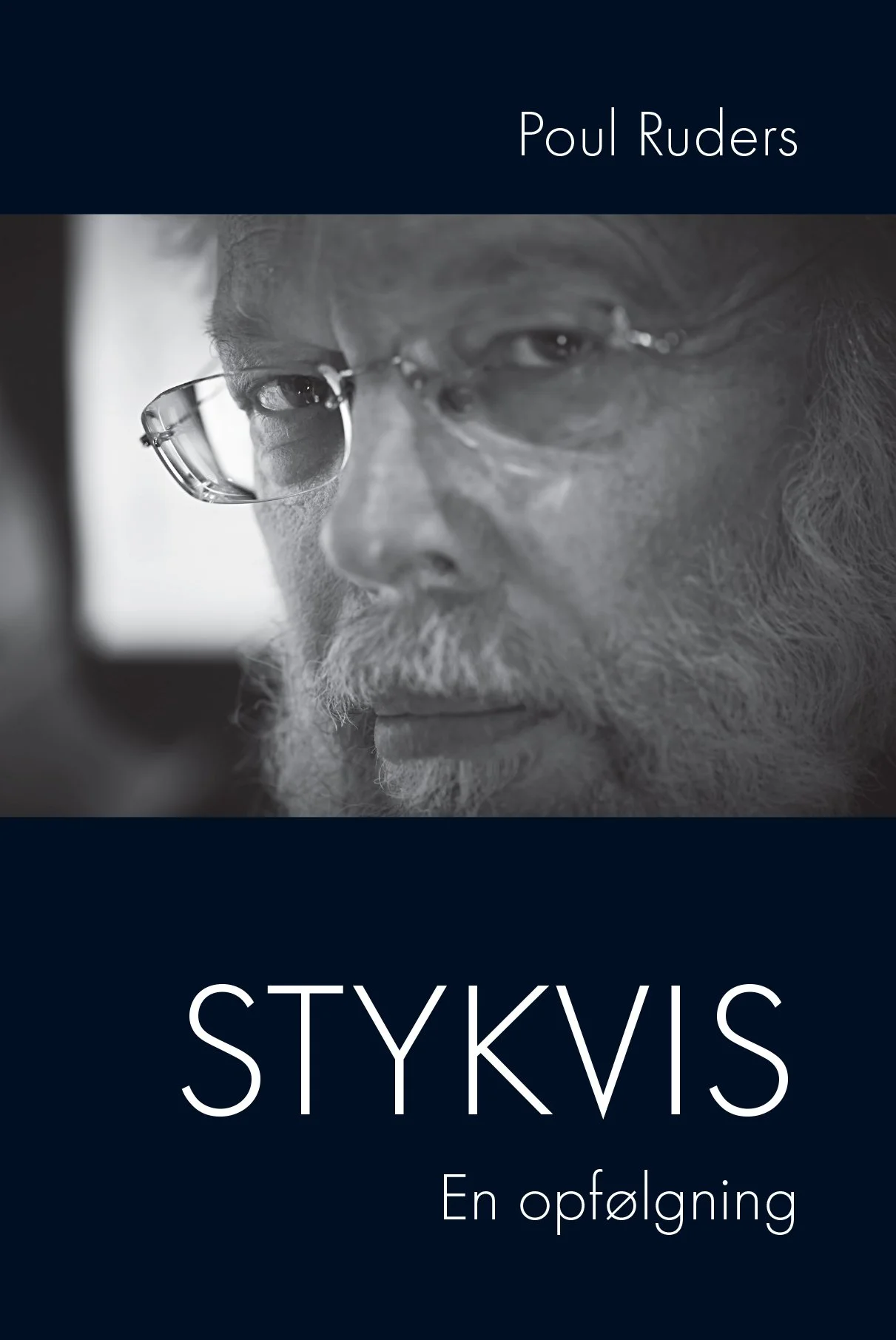

The following is a translation, from the original Danish, of the composer´s 2024 book "Stykvis", in English "Pieces", the personal story behind 10 selected compositions, from 1967 to the present day

Cover photo: Lars Skaaning

Introduction

“You could make a drawing of me like the ones slaughterhouses show of pigs, where it says ham, neck, shoulder, and so on.”

— Poul Ruders (Danish Music Journal no. 6, 1985/86)

The musicians float freely in mid-air, gravity suspended. The accordion virtuoso somersaults several meters above terra firma. The young female star on the violin—the record company’s latest darling—photographed with pouty lips, casts languid eyes over her bare shoulder. The conductor hasn’t shaved for days and appears solemn with half-closed eyes.

Welcome to the enchanting world of classical music—or rather the world as it appears on CD covers, in program booklets, and on websites. The stuff has to be sold, after all. Youth (that golden calf around which the panicked music industry frantically dances) must damn well learn to understand and love, until death do them part, the supreme position of classical music in a brainless world of noise, nonsense, and pop. Come on in—we’re much better than our reputation. Classical music isn’t boring at all. Believe us, it´s dripping with sex and rhythm until dawn. Whoopee! Off we go.

And it’s true—no other music has more to offer. A bottomless treasure chest of beauty, drama, wit—everything the heart, brain, and ear could desire. And yet, classical music (the word classical itself is a disaster, reeking of graduation caps and black suits) has been placed, once and for all, on a pedestal, from which it looks down upon the poor sods who haven’t been admitted to the innermost sanctuary.

The Swedish satirist Albert Engström once captured this skewed relationship in an unforgettable cartoon: A stiff aristocrat in white tie, monocle and cigarette holder, says to a friend—probably the doctor—after a fine dinner in the gentlemen`s smoking room: “…tell me, you who frequent the lower classes—do they have pianos down there?”

Intellectual condescension whenever “culture” comes up—a disdain often rooted in abysmal ignorance of “other” lives—is nothing new. The Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki (1933–2020) once remarked in an interview that classical music, like philosophy, is not for everyone.

What if he was right? A depressing thought. I don’t buy it. Music and profound thought are for everyone—or at least ought to be. There’s nothing in the constitution that says only children of doctors and lawyers may play the piano or violin. Or study at university. Still, I’m well aware that social background largely determines which path we follow in life. And that’s where the exception appears: deviation from the social heritance.

At high school I shared a class with a boy whose father was a construction worker and whose mother was a homemaker. Their circumstances didn’t allow for philosophical contemplation, and Bach and Beethoven weren’t exactly household names. And yet classical music (which made up a huge part of the curriculum at Sankt Annæ Gymnasium, from which we both graduated in 1968) came to mean the world to my friend.

Because he was musical.

And that’s enough. But what musicality is, and where it comes from, I have no idea (and I’ll steer well clear of the “roaring forties” of the “nature versus nurture” debate). Let me start with myself, as the dog said. Why do tears spring to my eyes the moment I hear the opening chorus of Bach’s St Matthew Passion? And when we reach that majestically rising bass line a few bars later, I’m done for. The choir enters, and I’m reduced to a wailing wreck.

It’s not the story that follows over the next three hours that brings me to my knees. I’m equally undone when I hear the slow movement of the secular Concerto for Two Violins. But the St Matthew Passion—the greatest musical work in Western cultural history—is the deepest, most unfathomably moving dramatization of an event that… never happened (I write this entirely at my own risk!). “Without Bach, God would be a third-rate character,” as the Franco-Romanian philosopher Emil Cioran so aptly put it.

And still, I have no explanation for why music “does something” to me, and has done so since I cut my first teeth. In my childhood home there was a piano, where my mother (who had learned to play as a young girl) would sit, though rarely. That she was musical is beyond doubt—she also had a fine singing voice. My father, who didn’t grow up with a piano, nonetheless acquired and enjoyed gramophone records (the old black shellac discs spinning at 78 rpm, later LPs at 33 rpm), with music mostly by Haydn and Vivaldi. And his father, a level-headed businessman, loved the operas of Verdi and Puccini. He came from the humblest of backgrounds in northern Jutland—so where did he get his musicality from? It wasn’t just the stormy heights of passion that drew him to the theater. Genes always surprise us.

Some people hum and whistle a tune the moment they’ve heard it. Others definitely don’t—perhaps the same ones who can’t tell whether an interval goes up or down. Are they unmusical, or tone-deaf? Not the same thing. Or is it? In Western culture, tonal music (the system of major and minor keys) has only been around for a little over three hundred years—a blink compared to modern mand´s 300,000 years on Earth. (In my autobiography “Would you believe it” I put it at 150,000 years, based on consultations with Moesgaard Museum, but newer research doubles that span. The Homo sapiens model at the museum has since aged another 150,000 years!)

The Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg, credited with inventing the twelve-tone method (placing all twelve chromatic tones on equal footing), was convinced that street urchins would be whistling his atonal melodies in his own lifetime. Needless to say, that didn’t happen.

My professional choice, however you look at it, is rooted in the joy of the kind of music written by white men, long dead, mostly German and Austrian. Classical music again (which of course includes the atonal repertoire too). But that still doesn’t fully explain why I am the way I am when music plays.

Once in an interview I claimed, “…I’m ridiculously musical.” It may sound a bit cocky, but I smoothed it out by continuing: “…in the sense that music never leaves me alone. Everything goes in one ear and stays there.” That’s not especially advantageous for a composer, who needs a clear head. So in daily life I’m very, very selective about listening to music. In fact, I almost never listen to any—especially not when I’m composing. Just reading the title of a piece I know is enough to trigger the inner soundtrack. Goodbye, sleep—for several nights in a row.

In my quickly read autobiography I tell about my life as a composer and how I gradually found my footing in this peculiar trade. Out of the many works from 1967 to 2018, I only delved behind three in detail: Psalmodies for guitar and chamber ensemble (1989), the orchestral Concerto in Pieces (1995), and the opera The Handmaid’s Tale (1998).

In what follows, I’ll try to recall the events, coincidences, personal encounters, and inner reflections (including frustrations) that accompanied the composition of the following works:

• Monodrama (1988)

• Symphony No. 1 (1989)

• GONG (1992)

• Serenade on the Shores of the Cosmic Ocean (2005)

• Sound and Simplicity (2018)

• Light Overture (2006)

• Handel Variations (2009)

• Harpsichord Concerto (2019)

• The Thirteenth Child (2016)

• Three Letters from the Unknown Soldier (1967)

What follows isn’t technical analysis but rather my own reflections on what it really means to compose—not only these works but composition in general. For those craving detailed analysis, I highly recommend Per Erland Rasmussen’s 2007 monograph Acoustical Canvases: The Music of Poul Ruders. The book covers my music from 1967 through The Handmaid’s Tale (1998).

In the bittersweet British film Venus (2006), Peter O’Toole plays a once-famous actor now spending his remaining time in the pub with another has-been actor, reading obituaries of their peers. They discuss how much column space each one got, how far into the paper the notice was printed, while speculating on how much attention they themselves will receive when their turn comes.

I haven’t quite reached that stage yet, but I’ve passed 74, and not long ago I read in an English-language article that I’m now “a grand old man.” Let’s repeat that… no, I can’t bear it. When an artist—composer, author, director, actor, etc.—is branded a “grand old man,” that’s the end. I picture myself as an old geezer in a rocking chair on the veranda, eyes watering, wrapped in a thick blanket tucked around my legs by the missus, mumbling about the good old days when…

… I, on New Year’s Eve 1987, dropped my luggage on the floor in the empty apartment in a modern housing complex by Columbus Circle in New York City. The apartment, an ordinary two-room affair that at the same time doubled as the US Office for the English music publisher in London, Chester Music, a sister company to the music publisher Wilhelm Hansen in Copenhagen, had been placed at my disposal for a couple of days, as a “base,” before I moved more permanently to an apartment in Brooklyn, which I had rented for three months. My “exile” sprang from a wish that had lain and fermented for a couple of years at the back of my mind, to set myself up and work in New York for at least three months, or more precisely, the 90 days a tourist visa permitted. On the home front my marriage to my then wife Helene had gone pear-shaped,, but we had not yet divorced, lived each on our own. She at our former shared house in Virum, while I bought and set up shop in an apartment in Burmeistergade at the Copenhagen borough of Christianshavn.

And it happened in those days, the spring of 1987, that I received a commission for a composition from the Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra, RSO, more specifically a percussion concerto with the orchestra’s virtuosic percussion master Gert Sørensen in the “leading role.” The premiere was then supposed to happen with much ado, as part of the Danish Composers’ Association’s 75th anniversary, 5 December 1988.

At that time, 1987, I was still organist at Mariendals Church in Frederiksberg, so I could not just up and leave to stay abroad; I had to apply for leave from the post—and it was granted. The apartment on Christianshavn I sublet to a grand- cousin.. When he asked me whether he could move the furniture around while I was away, I said: “… no problem, you can shove the sofa out in the bathroom if you wish, as long as it stands where it stands now when I come back!”

Chester Music’s office in New York had for several years been led by the Englishman James Rushton, and I had myself on several occasions lived there as his guest (free hotel, if truth be told), because the apartment also doubled his home.. There was everything necessary, kitchen and bath, two toilets and guest room. In other words, I felt at home when I put the key I had been given down at the porter’s, the doorman, into the key hole.. James Rushton had in the meantime been called home to the London office, and the position as Chester Music’s man in New York had now been transferred to a native New Yorker, a Mr. Copeland, who in the months before my arrival had sought—and found—an available apartment for sublet and immediate takeover in the borough of Brooklyn, one of the five so-called boroughs.

Why I had chosen precisely to begin my temporary exile on New Year’s Eve remains uncertain. I arrived at the high-rise complex The Beaumont in West 63rd Street, around 10 o’clock in the evening, and things were already heating up for celebration down on the streets. I stayed, however, “at the office,” all alone, for the new branch manager lived elsewhere. The apartment now functioned solely as an office. When I could sense that the inevitable jet lag had begun to creep up on me, I had more need for pillow and duvet than pranks on Times Square.

The next morning I hoisted up my unusually large, heavy, and clumsy duffel bag, which I had bought at home at a surplus store, and set course for Brooklyn Heights. Since I had been in New York several times before, I knew exactly which subway ran under the East River and into Brooklyn. Line No. 2 Express from 72nd Street, or the “milk run”, line no 1 from Columbus Circle.

I had arranged a meeting and handover of the key on site with the owners, Carol Weaver and her husband, during the course of the morning. I did not know them, for obvious reasons, but we “clicked” well, and after having been thoroughly instructed in how washing machine, stove, et cetera, worked, I was left to myself. In the literal sense of the word. Only very, very few people knew where I now was, here on New Year’s morning, 1988: State Street no. 10, Brooklyn Heights, NY, NY. E-mail, Internet, and mobile phones lay far out in the future, and my only technological access to the outside world was an ordinary landline telephone.

I had come primarily to write a larger work of half an hour’s duration, preferably finished during the three months I was allowed to be in the USA, so there was no time to waste, so better get fracking right away. It would, after all, have been obvious, had I stipulated that a piano be installed in the apartment, but I didn´t

The work I intended to write during my stay in New York was, in my inner “archive,” already sketched for percussion, a lot ofpercussion, and symphony orchestra without violins and violas. But still, surely a piano is alpha and omega when one composes? Not necessarily. It is difficult to understand if one is not oneself in the trade, but a composer “hears what he sees,” can immediately hear with his inner ear how it sounds, what he writes down—should preferably be able to hear it, and more than just approximately. It certainly does no harm just to try out whether everything is now “hunky-dory”. But here, in the present case, where the emphasis lay in the percussion, I was more focused on the rhythmic progression, timing, a carefully calculated time course, a journey in sound, from start to finish, without pit stops in the form of movements and sections along the way.

That required meticulous planning on graph paper, so that was part of the “equipment” I first unpacked and laid in a neat pile to the right on the folding camping table, which was one of the few pieces of furniture, plus a bed and two chairs, which the Weaver couple had left. But first I just had to go down and out into the street and get to know the neighborhood. There were shops enough, and restaurants, and a bustle of people in every desirable and conceivable guise. The nearest subway station was Borough, the first in Brooklyn on lines 1 and 2 from Manhattan.

There was a rich selection of pubs, many of them Irish, but there was no lack either of authentic American taverns. Even though at that time I was balancing, with great risk of falling down and hurting myself, on a tight and thin wire with harmless cozy drinking on the one side and… catastrophe on the other, I naturally also had to see whether there was a place I could “adopt” as my “ regular watering hole while staying in the neighborhood. There were several varieties to choose from, and my pledge not to come to grief in the three months was honored. There was only one thing on the program: to compose. But we must, then, just step inside at Moloney’s. The first thing that strikes one when stepping inside is the televisions running up on the wall behind the bar and in the corners. But always without sound. On the one screen one sees two large half-naked, sweating louts jump around in gaudy underpants while they punch each other in the face; on the next screen a bunch of giants toil and push around on skates while they all the time try to hit one another’s shins with some long flat sticks. I look around the room, which is not even half filled with customers. The few who sit at the bar are not looking at the televisions but are reading the paper or something that looks like racing sheets.

It is the middle of the day, and the lunch rush can surely not be long in coming. Lunch, midday meal…

For the likes of me, too lazy to stand in the kitchen and cook for just myself, New York is exactly the right place. Everyone is busy, rushing around from one meeting to the other, there is big business everywhere, so many New Yorkers never cook at home but get it brought in, call out for food, or take it home directly from a restaurant or a delicatessen.

At that time, in the late eighties, a Korean food chain had great success with their concept: fresh vegetables stacked up in tempting pyramids outside; inside one could take a foil tray at the entrance and then help oneself, with everything stomach and palate could desire, from an enormous buffet in the middle of the room. It was delicious, the selection almost endless, and… cheap. So it was not long before I became a regular down at “my” Korean on the corner. Unfortunately, only a few years later, competition broke out among the different shops in the chain, a situation that escalated and ended in violence and vandalism, and the chain as such was dissolved.

But of course I had come the long way to compose, not to lose myself in noodles and fried squid. Up in the apartment on the second floor the necessary papers, erasers, and sharpened pencils now lay ready and waited for me… who also waited for them, my tools of the trade, so I sat down at the camping table and… began.

Music moves in time, that is no secret, but as is well known no one can explain what time is. Albert Einstein once said that the sense of time as something that moves horizontally from one place to another is an illusion, albeit a very convincing illusion. Time does not exist, time does not pass, it is we who pass—all of it fascinating and without doubt correct. I am not a natural philosopher or cosmologist and promise to keep away from further speculations. But one thing is certain: when we sit in the chair in the concert hall and listen, then the illusion of time as something tangible, progressive, is not an illusion but a reality. We have all sat and writhed in the seat and looked, groaning, at the clock when a piece seems endless (and it will always be music we do not like): isn’t it soon over, for heaven’s sake… this is taking far too long, get it over with. Conversely, when music that really grips us stops before we think it ought to, then the work is too short! (It is almost a rule of the thumb, that when a piece by a living composer lasts more than half an hour, the reviews say that it is too long. One may harbor the suspicion that the composer thinks he is somebody, whereas when there´re hour-long tooth-pullers by Bruckner and Mahler on the menu, well, that´s all okay, for they are… classics!). Nevertheless, in the face of those considerations, I was determined to write a work of half an hour’s duration, beginning almost inaudibly, and which was slowly to build itself up toward an orgiastic climax, and I must, must, must absolutely not give in, slacken the reins, cave in and seek harbor before time (that was a little metaphor mix for the evening coffee…).

Timing, timing, timing!

Graph paper? That does not sound particularly musical, but that was precisely what I needed when I laid the foundation, so to speak, for the whole progression. The music, ie. choice of tones (to rub in the self-evident), had to wait until the “floor plan” had been fully worked out. On the graph paper I could first draw long lines with pencil, lines which then again could be divided into bars. Then stopwatch and metronome.

It was my plan start way, way down in the depths, as mentioned before almost inaudibly, and then gradually turn up the volume, and patiently add more and more beats into each of the four quarter-note beats in each bar, which was to constitute the only time signature in the entire piece (and came to do so). It is a widespread misunderstanding among composers today that the more notes one stuffs into each bar unit, the faster the music becomes. But it doesn´t. The result is a string of tone garlands, which indeed looks busy,, but fast it is not. The note activity within the individual bar division is indeed intensified, but the pulse is still the same, for example 60 beats per minute, which is not particularly fast. It is the pulse alone that decides whether the music is fast, slow, or in between. In 1986, during a visit to the Tanglewood Festival in Massachusetts, I gave a lecture for young composition students about “compositional endurance.” That is, how one keeps “the pot boiling” at the writing desk and the piano without keeling over. The emphasis was on how to write really fast music.

For that is “the test,” being able to write a hell of a lot of of notes, page after page after page, and the whole should then preferably progress smoothly. When you think that now at least five minutes must have passed and you check with stopwatch and metronome, the smile stiffens - not even a minute has passed! Then up in the saddle again. It is not for the squeamish. But it helps if one has a “plan,” such as a system which, from its own logic, sets the agenda. I myself for many years, right up into the late nineties, used the old English change-ringing system, where each (of my own “invented”) passage indeed appears again and again, but never in the same place in the progression. The order is never repeated and stops only when the permutation (as it is called) has run its course and is about to start over. A system like the above, has nothing to do with music; it is pure number gymnastics. Since I myself suffer from a mild form of number blindness (dyscalculia), I not infrequently, in the many change-ringing-generated works, happened to “count wrong,” but discovered it in time, and if not, I made a virtue of necessity… that is, human intervention (it is said that Beethoven suffered from the same handicap, so I am in good company…).

I urged the young people to invent and use anything whatsoever within the bounds of the law in their efforts to write long courses with a fast pulse. All composers, high and low, have used systems, including the old masters. But naturally, the system must never be audible when the music plays. That is the real art.

When after a month of intense work I had “drawn” the progression, that is, the rhythmic ground plan, it was time for the tones. And there was no shortage of time in my self-chosen isolation. For I had truly shut myself in for almost three months, had only few visits, but did from time to time go out into the city to visit friends and acquaintances. There was no television in the apartment, only a transistor radio. A couple of concerts and a quick trip to the cinema - and two trips out of town: to Yale University and… Tokyo!

Before I went to New York I received an invitation from the composer Jacob Druckmann, professor of composition at Yale University School of Music, to stop by his class and tell about my music. Yale sits in the city of New Haven, in the state of Connecticut, only an hour and a half by train from Grand Central Station. The excursion could be carried out in one and the same day. And it was, a welcome break in the daily routine in Brooklyn. My presentation in front of Druckmann’s class proceeded by the book: blah, blah, blah, playback of a little music on cassette tape (!), polite questions from the group, polite applause—and bye-bye and thank you very much.. My visit must nevertheless have made a certain dent, for I was asked during the lunch break whether I might like to become visiting professor for a time in one of the nearest spring semesters. That did not sound half bad (yet another excuse to disappear into the blue). The project was realized in the spring of 1991, after I—again—was granted leave from my position as organist in Frederiksberg.

Back in State Street the notes awaited… the music was now to begin to take form.

It was back in the 1960s, in the high-school time and a couple of years onward, that the desire to compose began to grow and slowly dominate, in competition with the parallel project of becoming an organist. The latter one can learn, the first one is born to, but the road is long. For most. My designated route wound in hill and dale and through darkest nooks and crannies until I got “all my ducks in a row” with the chamber work Four Compositions from 1982. It may seem a bit suspicious that I so shortly after the piece’s success at its international debut in London, 1982, was invited to teach at a prestigious American university and received large commissions for works from near and far. Four years later my orchestral work Manhattan Abstraction, conducted by Oliver Knussen at the Tanglewood Festival, was performed. Then things moved fast, Corpus cum Figuris with the New York Philharmonic and what have you; the gates toward golden times stood wide open. I had indeed established myself solidly, both at home and abroad, but it was—and still is—a journey with obstacles, mostly obstacles, placed by myself, in front of me. Today any idiot who has learned to notate music and with some rudimentary technique and knowledge of the instruments can in fact get away with anything—and even achieve success! In other words, because composition has been watered down as a subject, not to mention as an art form, has become too easy, it is imperatively to make it difficult again, to raise the bar for oneself.

From time immemorial (when I was an idiot, even without the most elementary knowledge of the instruments), and I myself slowly began to try my hand in the trade, it did not take long before I

ran into the wall that at all times towers up before all composers: how do I move ahead without grinding to a halt? Even today, when I undeniably have great experience (some would say: and with my whole future behind me), the process of getting from A to B to C, etc., is still a challenge, and it ought to be so. Something must continually be “thought up,” and this “something” should preferably be worth listening to. That simply and squarely is how linear composition can be defined. The horizontal composition process belongs to Western musical culture. In the Orient time perception was and is, also in music, completely different. The Japanese composer Tōru Takemitsu (1930–1996), who wrote (for the most part) for Western ensembles and orchestras, nevertheless maintained, and with colossal conviction, the vertical music perception, method, or whatever one wishes to call it. For he was precisely formed by the Oriental tradition. He said himself about his music that when one listens it is like a stroll in a Japanese garden, where one stops all the time, admiring the various fine things, a little bonsai tree perhaps, a charming bridge that arches over a brook, a pagoda, a fish pond, etc. Only very few composers formed by the Western tradition have, with success, been able to relax the horizontal regimen and compose more in sections that are not necessarily intimately and logically connected, that is, where A naturally gives rise to B, which again, etc. Claude Debussy, Igor Stravinsky, and the Frenchman Olivier Messiaen are the three geniuses I will claim have created works that revolutionized the structural form in Western music.

So there I was, after a month of intense rhythmic construction of the percussion concerto, and was about to “add colors ”; now I had to face the music, literally.. It was my first attempt with separated construction, first “skeleton,” then “flesh” (but was used again during the preparations for my First Symphony), and I had from the start decided that the orchestra should lipstick closely -, I am tempted to say - up against, the percussion, almost like a second skin. The orchestral writing must at no point stick out and set itself free of the pulse and the rhythmic drive.

The music itself consists predominantly of scales that follow the growing activity in the percussion, which gradually begins to “warm up,” in order to reach the high point via colossal wave movements; the work’s absolute climax lies displaced, off-center, which I compose toward at full gallop, with a dagger between the teeth and a blazing pistol in each hand. There is “no mercy” to be had; we are definitely in the red zone. The work ends with 7 strokes, executed with the utmost force by the soloist, on the bass drum. But I still had no title, and the child must indeed have a name.

One evening when I sat and minded my own business down at Moloney’s, it struck me: MONODRAMA…

The year before I wrote a piece for piano and the English chamber ensemble Lontano with the Dane Poul Rosenbaum as soloist: Dramafonia, that is, drama-sound, likewise a composition with a soloistic “leader,” in reality a mini piano concerto, but of a wholly other, I was about to say loose and capricious, nature than the percussion concerto. Now I was coming to the end with an almost fanatical forced march without “holes,” so to speak. So what could be more natural than to continue with the opposite of the little, restless piano concerto—with a Single- or Mono-drama? It was here, in State Street, that the seed for my 3 Trilogies was laid: the Drama Trilogy, the Nightshade Trilogy, and the SolarTrilogy.

But the seed sprang from a literary inspiration. One of the first things I did, just after I had moved into the apartment, was to study the contents of the only “inhabited” bookshelf that remained. I am an insatiable reader of novels, and after having riffled through a couple, I came across a book by a completely to me unknown author, the Canadian Robertson Davies. “The Rebel Angels” it was called. I began to read, as always an hour before falling asleep. But I did not sleep; I became so absorbed by the book, which I learned was the first part of a trilogy, “The Cornish Trilogy.” The next day I found myself in one of the many well-stocked bookshops in the neighborhood and bought not only the rest of The Cornish Trilogy but also The Salterton Trilogy and The Deptford Trilogy. Robertson Davies has since then been one of my absolute favorite authors.

And not only because he inspired me to write trilogies myself…

We had now arrived at March, the third and last month of my stay in New York. In the summer of 1987, during a visit to England, I received a phone call from Louise Lerche, director of the Lerchenborg Music Festival. Louise was at that time in close contact with the Japanese pianist Aki Takahashi and had visited Japan several times. I was invited go with her and the composer Niels Rosing-Schouw to Tokyo the following year. Niels was to have an orchestral work Twofold performed and I… a piece for Alto Flute and Foot-bongos! Carnival. A highly peculiar program combination, but why not? And why not say yes to a trip to Japan, all expenses paid? So, still with a not entirely finished percussion concerto lying on the camping table, I flew to Tokyo with United Airlines from Kennedy Airport. 14 hours non-stop. That the entire New York City Ballet was on the plane added to the entertainment. We had hardly reached cruising altitude and the captain turned off the fasten seat belt sign before the ballet corps jumped over the seat backs, back and forth, did flip-flops in the aisles, so the flight attendants had to intervene and call to order. At Narita Airport I was then, according to agreement, to wait for Louise and Niels, who had flown over from Copenhagen via Anchorage in Alaska. They joined in the arrival hall precisely at the agreed time, and so did a driver hired for the occasion, who was to drive us to our hotel at the opposite end of Tokyo.

Which is big, very big…

The drive took 5 hours, and I had to pee like hell…

After the concert (I do not remember where and with which orchestra and who else played; the whole project was very low-key), where the program consisted of only Danish music: Rosing-Schouw, Ruders, Gudmundsen-Holmgreen, I had a couple of days to myself, during which I decided to put myself to the test, travelling on Tokyo’s Metro during rush hour. I had, like so many others, seen TV programs where white-gloved employees physically stuff people into the train before departure. They actually did; I had the pleasure myself… My primary goal for the day’s outing was, however, prompted by the wish to see with my own eyes the famous volcano Fuji. At the hotel the English-speaking receptionist could tell me precisely how many metro stops there were on the trip from the nearest station to the railway station from which a local line serviced Fuji-san. Since all signs were only in Japanese, the only way I could be sure to get off at the right station was to count on my fingers and hope that luck would favor the bold. It did. How I then found the right train in the direction of Fuji is still a mystery to me. But I found it—and arrived safely at the place where I was to get off to find the circular cable car bringing tourists comfortably and at a sedate tempo around the iconic mountain. And I really got to see it, which is far from certain, since the top of the volcano, the cone itself, is mostly shrouded in clouds. I was more than lucky, one must say. And miraculouslyI also succeeded, without getting lost, even after having jumped aboard a bus where the destination was written only in Japanese, in finding a nearby station where I could get back to Tokyo with the legendary high-speed train Shinkansen.

But of course I had to get home to New York and get on with finishing the percussion concerto. Upon arriving at Kennedy Airport I became slightly confused when I bought the day’s paper and looked at the date. But it was yesterday? How was that possible? Then it dawned on me: I had crossed the International Date Line and “won” a day. Precisely like Phileas Fogg in Around the World in 80 Days, which made it possible for him to be in the Reform Club on the right day just before the clock struck 12 and thereby win the wager. Had he traveled the opposite way, he would have lost.

It also happened, by chance, to be my birthday, 27 March 1988, so I had my birthday two days in a row! The last I celebrated in solitude, in my bed, knocked out by a more than ordinarily violent jet lag. That, and a strong sleeping pill, meant that I could sleep 12 hours straight. It helped, but my time in New York was about to run out, and I had not completely finished with Monodrama, but leaveI had to.. True, I was not entirely finished with the piece, but the score had accumulated considerably,, so it´s hardly that I took it with me up into the plane. I would have none of having it stowed in the hold in the duffel bag together with a mountain of other people’s suitcases. I had no copy, so I sat with the many manuscript pages on my lap during the long trip home. I let myself into the apartment, Burmeistergade 3, 5th floor to the right, now after almost 3 months abroad. The sofa stood where it stood when I left…

The concert where MONODRAMA was to be performed was set for 5 December the same year, so there were not oceans of time left. I managed, in relatively short time, to complete the piece by hand, not printed (that was long before computer engraving was invented), but photocopied and passed on to my faithful parts copyist Ole Thilo. He then wrote out in separate booklets (the so-called parts) by hand what each individual instrument was to play.

The concert itself was on the verge of being cancelled, as the conductor Michael Schønwandt had contracted tonsillitis and was in an extremely bad way. The conductor Frans Rasmussen was called in as possible eleventh-hour replacement. Schønwandt would not give up, however, swallowed a mountain of pills, and the concert, which besides Monodrama also offered works by Per Nørgård, Rued Langgaard, and Carl Nielsen, proceeded as planned.

Was I myself satisfied with my work? One is never completely satisfied; there is always something, always a pebble in the shoe. As, for example that I, when the music had begun to grow, could not restrain myself from borrowing from myself a passage from the prelude to Act 2 of my capsized opera Tycho, Stjernemusikken(Atar Music). There is nothing wrong with the music in itself, but it deflated the intensity a bit. Fortunately, it appears for only a short (more or less) time, and I “repaired the fence” again.

In the program note, that is the “user guide,” where the composer writes a little about what he has envisaged and which is printed in the program, I had written the following, not a little aggressive, manifesto:

“As a composer I do not believe in music’s direct function as social transformer or usurper.. But music’s unique inherent, indirect metaphysical power gives the composer the possibility to rattle the bars and shout at the prison guards: the bureaucrats, the politicians, the reactionaries, the philistines, the xenophobes, the polluting swine, the prophets of cutbacks, all the generals behind the cultural nuclear winter that has laid itself over the Denmark of the time.”

At the subsequent party in the Radio House canteen I was accosted by an indignant Hans Jørgen Jensen, who at that time was Director-General of all of Danish Radio. He, who was both politician and bureaucrat, was offended by my furious manifesto and scolded me. Then I gave him yet another dressing-down, and… he laughed! We made peace and in fact became good friends who respected one another in the following years, when he sat in the director’s chair.

MONODRAMA has only been performed twice up to now. The solo part can only be played by a percussionist from the absolutely top international drawer, and the orchestral instrumentation (the slightly out-of-the-way requirement not to have violins and violas) and the setup in two instrument setups: one to the left, one to the right, and the formidable deployment of percussion in the middle, means that the piece does not exactly offer itself.

But there exists a frequently performed solo version, where only the percussion appears: Towards the precipice, arranged by precisely the percussion virtuoso Gert Sørensen, he who was responsible for the premiere that December evening in 1988. He has recorded the solo version, together with my remaining percussion works, for the record label DaCapo.

Which also, in 2009, released the entire MONODRAMA, with yet another percussion star, Mathias Reumert, Aarhus Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Thomas Søndergård. Immediately after my return home from New York, the Danish music publisher Wilhelm Hansen was bought by the American publishing giant Music Sales, which also, in the same mouthful, gobbled up WH’s English sister company Chester Music, and it is precisely here, in the English capital, that we are to visit in the next chapter.

SYMPHONY No 1

WODKA RESTAURANT: HIMMELHOCH JAUCHZEND FOR POUL RUDERS

SEPTEMBER 3RD, 1990

SELECTION OF BLINIS - PIEROGY FILLED WITH CHEESE AND MINT CHILLED SORREL SOUP - SHASHLIK WITH KASZA FISHCAKES WITH DILL SAUCE FILLED WITH SAUERKRAUT, KASZA AND MUSHROOM - SORBET.

POACHED PEACHES WITH CHAMPAGNE SABAYON

Far back, in 1970, in the Jurassic era, when I studied organ as main subject with Finn Reiff and instrumentation with Karl Aage Rasmussen, both teachers at the Funen Music Conservatory in Odense, I had a composition accepted for performance in the Great Hall at Odense Town Hall, a composition that I had struggled with, unsolicited, but with great enthusiasm, a piece for piano, cello, and oboe. At that time I was a totally blank page, knew nothing, could do nothing, but, as the saying goes: where there is a will, there is a way. I was 21 years old and, not unusual for that age, emotionally excited, romantically-idealistic, not a little puritanical, prejudiced, over-sensitive and panting for Sturm und Drang. It was also at that time, the transition between the 60s and 70s, when cracks had begun to appear in the otherwise so firmly cemented compositional avant-garde, which for the most part had goose stepped through the 50s and 60s, through Europe, from the strongholds of modernism, such as the “boot camp” in the South German city Darmstadt, with its irreconcilable demand for renewal of the material at any cost – and absolute rejection of any thought of writing tonal music.

That was just up my street, I who, ideologically solidly padded between my two blinkers, developed, zealously, an intolerance toward those who thought differently.. Music couldn´t become extreme (and ugly) enough.

It was also at that time that the Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki’s music appeared to me as the definitive example of how far out into the extremes one could go, works such as Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima and the String Quartet, both from 1960. In the quartet, strings are not bowed in the traditional way, instead the bow is used as a hammer, with which one beats on the strings and everywhere on the instrument itself, on the wood, front and back, on top and underneath. Now that was something!

But it was also the same composer who aroused colossal uproar in true-believing avant-garde circles by ending an otherwise completely atonal and wildly experimental work with… a C major chord! Even today the effect is striking (and brilliantly conceived), also back then, in the late sixties, but it did not dawn on the frothing, blind-with-rage modernists that what they had just witnessed and heard was… re-thinking and at the same time true avant-gardism.

Back in Odense, at the Conservatory, an old villa in Kronprinsensgade, I had persuaded three fellow students, the musicians Inger Marie Thomsen on piano, Erling Thorborg with his cello, and the oboist Ebbe Monrad, to participate in my new piece. I cannot recall who had arranged the concert in the Town Hall, but can still remember that the program consisted, besides my piece, among other things the premiere of Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen’s Plateau pour Deux, for cello and old-fashioned car horn! The remainder of the program is lost in the mists of time.

My piece had been given the title: Himmelhoch Jauchzend – zum Tode Betrübt. So, Sturm und Drang with a vengeance. It also raged in the music, where I, as the modernistic hotspur I was, among other things managed to place my father’s old electric (and to the mains connected connected) shaver down on the strings of the grand piano (the whole lid had been removed), the pianist was also asked to throw a 200-gram brass weight (from my father’s flower shop) down into the piano. There was almost no “real” playing on the keys, and what went on in oboe and cello was likewise not for the wimpish.. I “conducted” the course of events myself, i.e., gave signs for when the individual musicians were to “activate” my strange inventions. For some reason I also remember the clothes I wore. Blue windbreaker and jeans! It was, after all, right in the middle of the youth rebellion, where one was supposed to dress as casually as possible, preferably a little sloppy and thus show one’s contempt for the bourgeoisie. If I had shown up in suit and tie (in fact I owned both, but did not tell anyone), I would immediately have been branded as a fascist.

Fashion has undeniably changed since then…

The score consisted of some large A2 boards which I had filled with cartoon-like symbols à la Ka Pow!!! …and an exploding star or two. But the title? Selected literati will recognize the quotation from Goethe’s poem “Freudvoll und Leidvoll” from Egmont, the song which the female main character, Klärchen, sings:

Freudvoll

Und leidvoll,

Gedenkenvoll sein;

Langen und bangen

In scwebender Pein;

Himmelhoch Jauchzend,

Zum Tode betrübt;

Glücklich allein

Ist die Seele, die liebt.

Now, that was quite a mouthful for a 21-year-old budding composer. I probably didn´t understand much of the poem, but used the two lines Himmelhoch jauchzend, zum Tode betrübt as the title of my little, “cry-to-heaven” pathetic piece. Which of course has disappeared from the face of the earth (but I do believe that I have heard that the score-boards are in private ownership somewhere. But it is not with me…).

We fast-forward from 1970 to 1989, the year I turned 40. In my calendar from back then, it says laconically in the space for 27 March: “40 years. Well…”

PRESTO JUBILANTE - TRISTE - FURIOSO FANTASTICO

Shortly after my return home from Brooklyn, I received my first truly prestigious commission: a large orchestral work for the BBC Symphony Orchestra, for premiere the following year at one of the famous Promenade concerts in Royal Albert Hall. Oh my God! Himmelhoch Jauchzend, zum Tode Betrübt, at least the first, rejoicing to heaven, but certainly not sorrowful unto death. But still, it was tempting to haul the title of the almost twenty-year-old “Town Hall piece” out into the light of day and… use it as subtitle for a symphony!

In my school years, as a member of the Copenhagen Boys Choir, I took part in the performance of Bach’s Christmas Oratorio. The text in the introduction to the first of the six cantatas that make up the oratorio begins: “Jauchzet, frohlocket!” And quietly I began to sense the outlines and the content of a mighty movement for large orchestra, the whole thing setting out with the first bars of precisely Bach’s Christmas Oratorio. My past pushed me,, one can say. But the joy in the first movement (of the symphony, which was to end up appearing in four movements) is limited. It is powerful and fast music (the beginning of the movement is a hurricane of energy and merciless propulsion), but behind the rejoicing hides desperation. Quite concretely because I mix Bach with “wrong” tones; Bach does not appear clearly, it is an impossibility. It would be a lie. In an interview in connection with the premiere, I said in an interview on DR:

“I have spent nine months, that is, an ordinary human gestation period, to write the symphony. A composer operates with two concepts of time: namely the final, sounding time, which in this case is 35 minutes, and then the momentary composing time, which is a kind of compositional slow motion. One freezes down one’s sense of time, but at the same time becomes completely aware that when one spends a whole day, then what one has finished composing, when darkness approaches, lasts only one or two minutes. And if there is not some sort of plan beforehand, then it can very easily go wrong. When I was to get started with the symphony, I simply sat down with stopwatch, metronome, and a pad of graphed paper and drew the first movement and its linear course. I forced myself, in a kind of vision, to see the entire course in front of me on a line. It took about a month. It takes a very long time to get the proportions properly set down, so that one can leaf through and see the course. There is not a tone. The tones, notes, come later. But the tensions and relaxations, the entire construction course, the bearing pillars, as when one builds a bridge – all that must be in order before one moves out with bricks or mortar or whatever is used for bridges today. Then one can begin to compose a large orchestral score. I am interested in the long courses, in the challenge itself of having control of my own feelings – to put it very simply. I think that is incredibly fascinating.”

So I said 34 years ago, and although today I am far more spontaneous (perhaps because having composed for so many years simply makes it a bit easier to write “from the hip” and get away with it), both then and now it is a fascinating process.

That my first symphony waited to be picked up by me until I had turned forty is no coincidence. Symphonies come and go, and have done so since Haydn and all the way up to the beginning of the twentieth century, where the dawning modernism rejected the phenomenon of the symphony, that is, a weighty, usually multi-movement narrative in music for orchestra, as untimely, even plainly reactionary. Nevertheless prominent composers continued through the twentieth century, people such as Prokofiev and Shostakovich, to write large orchestral works, conceived and published as numbered symphonies. Sibelius and Carl Nielsen wrote their symphonies totally isolated from the modernist tumult out in the wide world. Vagn Holmboe likewise composed undauntedly symphonies through the 1950s and 60s.

In the 70s and 80s Per Nørgård wrote his symphonies, admittedly with one ear turned outward, but without lapsing into modernist excesses or falling back on the virtues of times past (a certain cold-sweat-inducing rhythmic complexity cannot, however, be denied to mark works such as the 5th Symphony, written for the Radio Symphony. During the rehearsal work the following witticism spread among the musicians: “…to learn this piece is like threading a needle with both hands tied behind your back, and at the same time swallowing a blue whale.”). But back to the old virtues, the grand master of the classical four-movement symphony, Johannes Brahms, was forty years old before he dared to tackle the genre (he heard the mightyt Beethoven’s giant steps behind him all the time…). Since I had now myself rounded the two score years, I thought I could probably defend writing one, or at least calling a larger orchestral work a… symphony. Quite soberly the word has root in Ancient Greek and can probably most easily be translated as “concordant in sound” (the very concept of symphony in music-historical context is, however, more complicated and belongs outside the frame of this narrative). But that did not hold back the self-appointed symphony-haters. I have listened to and read anti-symphony manifestos delivered by furious, sputtering composers, not only from the so-called progressive camp, but also from another, more sedate quarter (in most cases composers who themselves would like to – but could not – write a symphony). When all is said and done, it is perfectly immaterial what the “child” is called. And today one can call any piece of music a symphony. Symphony for theorbo and washboard? Not a problem, there are no longer any rules about sonata form and development section and recapitulation and adagio and minuet and scherzo and finale and the devil and his aunt. In literature it is the concept of the novel that has been both killed and revived through the years after the Second World War. Today more novels are written than ever before.

Now, about to write about my work on the symphony, I whipped out, as previously said, my diary from 1989 from the shelf, in the hope of finding just a little about the process, how far I had gotten this and that day, whether I had talked with anyone on the telephone about the piece, hastily jotted considerations, etcetera. Not so much as the shadow of a living sound. Nothing. Which surprises me a bit, but I will think that I simply wrote away, ie. first timing, then notes, from morning to evening, without any need for some internal “briefing”afterwards. One thing, however, is certain: I still lived in the apartment on Christianshavn. Where, incidentally, there stood a piano, which this time I used more than just sparingly during the work of composing the first movement.

The graph paper was replaced by ordinary sheet music paper, oblong, and with stave systems enough on the page that I could isolate two systems at a time, just as one sees it in piano music. In other words I laid out to write the draft, which I could then later write out for large orchestra. In the trade such a draft is called a particell. I wrote down all the notes, every single one, in a sort of reduction for piano, but long before there was any orchestra to reduce. My inborn (shall we not call it that?) ability to hear the entire orchestra in my own head, just from looking at the simple “reduction” on two stave systems, made the work with the instrumentation afterward not exactly a walk in the park,, but into a mentally and physically absorbing process.

My idea to open the “show” with a direct quotation from precisely the beginning of the Christmas Oratorio was now to be realized. First in draft form, then in full orchestral score. The very technical and formal construction is thoroughly and excellently described by Per Erland Rasmussen in the monograph Acoustical Canvases. What you can´t read there is what the composer actually thought about during the work on the piece. Only I can lift the veil on that. I will then attempt to do so.

In the chapter about the percussion concerto Monodrama I write about the most basic question for a composer: how do I get from A to B to etc. without keeling over? There is no answer to how one does it, unless the music is thoroughly predetermined, ie. follows a system that in advance tells how the points are to be connected, as was/is the case with the so-called serial compositions from the beginning of the 1950s. Pierre Boulez’s Structures for two pianos is a striking example. The very title says it all. The view is, however, more obscured and the road more impassable when one has only oneself as “tour guide”. And that was indeed the case in the apartment, 3 Burmeistergade, 5th floor to the right, in the spring of 1989.

I did, however, already have a couple of good cards on hand: the course, the form was in place, I had a title which in itself told a bit about what was to happen, and a musical point of departure, the opening bars of the Christmas Oratorio. So it was just a matter of getting started.

It is for obvious reasons incomprehensible for those who are not themselves composers (and here we can calmly include the entire population of the earth, minus a small per mille of odd but harmless types like me) to put themselves into how one creates music out of nothing. And it is precisely that: where does it come from? Countless are the times when I have disappointed people when they ask: where does the inspiration come from?

Each time I must say: “I have no idea.”

I am a walking, bottomless septic tank of ideas that just wait to be hauled up, aired, and called to order. In the concrete case, the symphony, there is, however, no doubt that both Goethe and not least Bach gave, perhaps not so much inspiration (which again is hard to define), rather a push forward, possibly toward the abyss, or over it. The latter should preferably be averted. Through my somewhat fragmented youth,, not least during the short stay at the Funen Music Conservatory, I acquired a (perhaps deserved?) reputation as an excellent improviser, that is, one who could sit down at the piano and just play anything of one’s own making out of one’s head. I could also “imitate” various classical styles on command. Atonal improvisation? Piece of cake! That is not all too bad for a composer to have up his sleeve.. The very act of coming up with something was (and is) not a problem for me. But that said and done,it is far from enough, and it does not take much parading on the keyboard before it becomes boring and irrelevant for anyone other than the soloist himself. But to possess the ability, as a kind of back-up support, when one is to compose for real, is a great help. But every single note must be justified (in the first instance to myself). It can be a toilsome process, but at times even long passages fall “into place,” more or less by themselves, and the notes make “sense” upon closer inspection. It quickly became clear to me, however, that if the Bach quotation (association) was not to stand out as “just” an empty gesture, I had to sneak other elements from the Christmas Oratorio into the movement, which gradually, in itself, began to take shape as an instrumental Christmas oratorio. It was therefore obvious to go on further “beachcombing” in Bach’s work, more precisely in Part 6, where Herod, in a recitative, hypocritically shows compassion with the newly born King of the Jews. The recitative I quote note-for-note, but I let the orchestra’s woodwinds “sigh and sob” in descending semitone intervals. In the middle section with the heading TRISTE, I “revisit” myself and pull out of the bag the oscillating chord alternation, B-flat minor–D-flat major, B-flat minor–D-flat major, in trance-like repetition, an idea which I used back in Monodrama. Now here, in the symphony movement, the chords lie, infinitely hushed beneath an innocent Christmas carol,, played in deep piccolo flute, where the sound almost resembles a recorder. Here I then, irrevocably, arrive at the first place in the movement where the contrasts between the ecstatic and the inward-looking truly present themselves uninhibitedly. The last minutes of the movement is a frantically raging “white knuckle ride” of symphonic desperation. Furioso fantastico.

TRANQUILLO MOLTO; DOLCISSIMO

The next movement appears as the definitive diametrical opposite to the first movement’s extreme contrasts, hinted at in the heading, which translated into English reads: Very slow; with the utmost softness. Almost nothing happens, and the movement lasts a little over ten minutes. The “almost nothing” again consists of the chords B-flat minor–D-flat major in an unbroken rocking back and forth, back and forth, in the whole orchestra, though with almost imperceptible rhythmic alterations along the way. There is also here a literary motto which tells a bit about both the mood as well as content, a quotation by the Czech author Milan Kundera: The desert of time / the terror of constancy (“there now… the desert of time stepped forth from the half-darkness, frightening and oppressive like eternity.”). One could affix the label “minimalistic adagio” to the movement, which in its apparent “emptiness” both irritates and confuses, but indeed also gives great peace and solace for others. Extreme simplicity can appear provocative, especially for composers and music reviewers who feel more “safe” when they can hide behind music that teems with activity… naked simplicity is too embarrassing.

SCHERZO PRESTISSIMO

“Ferociously fast and joking” is probably the best translation from the Italian. In the classic tradition the scherzo appears as the penultimate movement, as a sort of preparation to the mostly broader and more weighty last movement. Scherzo means joke” in Italian, but in this case, the joke belongs to the more sinister variety - and is over after two minutes. I decided that the transition into the Finale(with the uncommonly austere title “Death Masque”)should unfold as a whirling tornado of sound, full of percussion “thunder”. Like the second movement, the music is written directly in full score, no graph paper, everything was already lined up in my head. The trance like world of the second movement is being hosed off the table, preparing the way for

MASCHERA FUNERALE

…as Per Erland Rasmussen, very aptly, compares with an “extended scream.” In other words it is not a branch-line of Stars and Stripes…

Maschera Funerale, Death Mask… why that then? And not something more lively, not to say positive? It is tempting to say it is zum Tode betrübt that comes forward in all its despondency. That, and then the clear awareness I had regarding the balance in the entire symphony, seen from a “bird’s-eye view.” The enormous, tension-packed first movement up against stasis in the second movement, replaced by ultra-short violence – stasis again. End.

The balance between activity and stillness makes sense, formally, musically, compositionally. The entire movement, which plays for almost 10 minutes, consists – again – of only one chord, a towering chromatic affair that spans 6 octaves (that is almost an entire piano keyboard!). The chord is varied only “from within” with small changes, but the tension grows at the same time as the tempo becomes slower and slower. The plaster over the dead face congeals.. In the end the light is turned off completely, after a brief glimpse of the little Christmas song from the first movement.

The premiere was set for 3 September 1990, but the rehearsals for the Symphony had already started at the end of June the same year. I therefore flew to London so that I could be present at the first rehearsal, 27 June in the BBC Symphony Orchestra’s regular rehearsal rooms in Maida

Vale, a fashionable quarter, with canals and houseboats, in northwest London. The rehearsal rooms, which are still used by, not only the BBC, but by visiting orchestras who need extended rehearsal time before the concerts, are decidedly not fashionable. A dirty white, oblong building that most resembles a closed-down factory hall. But there is space for even gigantic orchestras with choir, soloists, etc.

The conductor was the Dane Michael Schønwandt, who had to step in when Oliver Knussen, who was originally to have conducted the entire concert, had to cancel for health reasons.

The Promenade concert itself on 3 September, which in addition to my piece also consisted of works by Béla Bartók and Hector Berlioz, was a, for me at any rate, tremendous event. And if the audience’s reaction and the subsequent reviews in the London newspapers are to be trusted, then my symphony also made a great impression on others than the composer.

But “impression,” what is that? It can of course be interpreted differently. The two static movements are certainly not everyone’s cup of tea, especially not the extremely simple, trance-like second movement. At a performance some years later with the Symphonisches Orchester Berlin (not to be confused with the “exhaulted” Berlin Philharmonic), the piece (and I) received bravo and hurras from one half down in the hall, and furious boos from the other. It is not unthinkable that especially the second movement was too much beyond the permissible. Precisely the same divided reaction I received ten years later, at the premiere with the “exhaulted”, ie. the Berlin Philharmonic, of my orchestral work Listening Earth. It is of course not particularly amusing to appear on stage after a performance and get BOO! shouted into one’s face by angry, upset people… but… as a colleague who was present, an American composer, said to me: “…I am jealous! There are not many composers today who can move people in that way.” Well, perhaps… one thing, however, is certain: I never write music that aims to please everyone, “applause-nicely-afterwards” music. That I neither can nor want.

The symphony, which is written for large orchestra, i.e., four of each woodwind (as opposed to the usual 3) and six horns, four trumpets (as opposed to the standard four for the horns and three for the trumpets), as well as a colossal array of percussion and two pianos, is not exactly sales-friendly. But it has nevertheless had performances after London, in Germany as mentioned, but also in the Netherlands. The Danish performance with the Radio Orchestra conducted by Leif Segerstam knocked the legs out from under the audience – and reviewers (there were, however, still some who were sore about that second movement, where nothing happens). The subsequent CD recording, with Segerstam and the RSO for the English record company Chandos, nevertheless went and became something of a hit(in 2025, the same recording was released by Bridge Records in a box set with all my six symphonies, 1989-2021)..

The year after the premiere in London, when I was well into my half semester as visiting professor at the Yale School of Music, I received a phone call from London. The symphony had been selected as winner of The Royal Philharmonic Society’s prize as best newly composed orchestral work performed in London in 1990. I had a plane ticket paid and flew over to the award ceremony, which took place in the Barbican, home of for the London Symphony Orchestra. I had just managed to get my statuette in hand when the doors into the concert hall, where everyone was gathered, burst open, and two police officers came running and drove the entire assembly out into the street. A bomb threat from the IRA had been phoned in, so everyone had to get away in a hurry. The RPS prize itself is an honorary prize, yes, yes, that´s okay, but I cannot pay bills with the honor…

As far as prizes are concerned, overall, there are those who wonder that I have received neither the Nordic Council Music Prize nor the American, likewise annually awarded, Grawemeyer Prize. The explanation is simple: both are competitions where one is nominated or submits a piece via a sponsor. And in spite of several requests and invitations to participate in both, I say no every time. I do not participate in competitions, do not line up with hat in hand. Besides, I am an uncommonly sore loser, so by not participating I naturally cannot win, but what is more important: I cannot lose!

But should someone get the urge, unsolicited, to let a prize drop down onto my head, I will certainly not stand in the way…

But I quite forget the menu that opens the chapter about the creation of the symphony; it is from a gourmet restaurant by the name of “Wodka,” where my publishing representative at Chester Music (now, like Wilhelm Hansen in Copenhagen, part of Music Sales), the completely incomparable Rosemary Johnson, had not only reserved a table, but also had printed, on embossed paper, the menu itself. The dinner was taken immediately after the concert in Albert Hall, in the company of good friends and acquaintances.

Without boo-shouts…

Shortly after the concert in Royal Albert Hall, my then wife Helene and I tried to patch the remnants of our shipwrecked marriage. She bought a ground-floor apartment in Rudolph Berghsgade, and I acquired a similar apartment just around the corner, 45 Engelstedsgade. Both apartments close to the busy thoroughfare Lyngbyvej at Hans Knudsens Plads. Then we could visit each other from time to time, now and then. It all went civilized enough, without any histrionics, tears, and gnashing of teeth, but the arrangement was of course doomed, and in December 1991 I moved to London (described in more detail in the memoir Would you believe it).

But it was in the apartment in Engelstedsgade that one day at the start of 1991 I read an article in Newsweek, an American weekly magazine that I subscribed to at that time. The article dealt with the Sun and its anatomy and behavior, among other things, that it vibrates, like a gong, and similar to the latter, the sun oscillates in many horizontal layers.

Now it was my turn to vibrate…

For some time I had been ruminating using the name of a percussion instrument as the title of a work, and here I had the title as well as a plausible “excuse” to use it; the thing with the four simultaneous vibrations was a stroke of luck, the ideal point of departure. Everyone knows what a gong looks like, it is big and round, and looks like the sun! Moreover, it is a curious coincidence that one of the ground-based sun-observing units is called GONG (Global Oscillation Network Group).

How, and where, I wrote the violent orchestral work GONG, first part of what came to be the Solar Trilogy, I will now tell about in the following.

I only rarely write music without someone having asked me to do it, that is, commissioned a piece from me. GONG was also commissioned, but I cannot remember the details, strangely enough. It must have been the Radio Symphony Orchestra, for the premiere took place at a

Thursday concert with them, in 1992, conducted by Leif Segerstam (not Michael Schønwandt, as it says in Acoustical Canvases). It was the idea that the orchestra take the piece on their tour to the USA the following year. But it was my much older work Thus saw St.John that was chosen instead. And why? Explanation to follow later on in the narrative…

Which began in London, more precisely at Tooting Beck Hospital, ward G (for geriatric). Not because I was ill or decrepit, I had only just turned 43, but through a couple of good friends, the pianist Rolf Hind and his partner Ray Rowden, top boss of the hospital in question, I could rent, for only 50 pounds a month, a couple of vacant rooms with all the necessary accessories, on the floor above the administration.

The piano was not included in the heavily reduced moving habengut I had with me from Copenhagen, so I had to go into town and look at a keyboard. At that time, at the start of the 1990s, there was a rapid development underway in, among other things, digital pianos, where the manufacturers made use of the technique, digitally recording the authentic sound of practically any conceivable acoustic instrument, which is then sampled, i.e., all tones, in chromatic order, are laid in on a chip, and the pianist only needs to press a button where, for example, indicating “piano” and then that´s sorted… the piano sound, mind you, which in most cases is of astonishingly high quality. Quality brands such as Yamaha and Roland were (and are) among the best manufacturers. Those were names I had been recommended from people who knew more about these matters, so I ended up buying a Roland with full keyboard (8 octaves), touch-sensitive, as on a real piano. There are many advantages to such a digital piano (not to be confused with a synthesizer): it never needs tuning and takes up far less space than a grand. With headphones connected to the instrument, one can, even if one lives in an apartment, play at all hours of the day, without getting the neighbors riled up.. And not to forget: it is far cheaper than an acoustic piano or grand. The best electronic pianos have sampled the sound from, for example, a Steinway concert grand, a luxury instrument that only the few can afford.

Before long my new Roland arrived at my, admittedly, not entirely ordinary address, and I began ever so tentatively to contemplate the new piece which I already had given the title GONG.

We shall, however, return briefly to New York, where I had been on a short visit earlier in the year, 1991. One day I walked past a shop selling music instruments, which in the window had on display an oblong wooden tube that resembled the iconic didjeridoo, the ancient wind instrument with its ill-omened but at the same time hypnotizing drone, which the indigenous Australian population uses at their ceremonies (everyone who has seen a Crocodile Dundee film will know what I am talking about).

The specimen in the window was clearly not an original didjeridoo, but a sort of tourist version. I nevertheless could not restrain myself, went into the shop, made inquiries, and was allowed to toot on the instrument. It may not have been the real thing, but, besides being easy to operate, the sound was astonishingly authentic. I bought the contraption, which measured about a meter in length, so it was relatively easy to lug along. And later with me to London, without having an inkling that I would use it in an orchestral work. I began to write the introduction to GONG, not violent and chaotic (I reserved that for later), but an extended course consisting of chords that are slowly built up from the bottom, and in the end suck themselves and the audience into the sun, and deepest down in the orchestra, together with double basses, I let the didjeridoo drone in a stubbornly repeated rhythmic pattern, vroom-vroom-vroom-vroom, one of four rhythm modules (oscillations) that recur throughout the introduction. The three other oscillations are taken care of by tam-tam, bass drum, and digital piano.

GONG requires a colossal array of percussion instruments, here just a selection, mentioned at random: bass drum, suspended cymbals, triangle, water gong, Chinese cymbal, vibraphone, anvil, tam-tam, Bali gong, water chimes, Brazilian reco-reco, spurs, etc. The didjeridoo and a couple of the percussion instruments were sampled by our friend from Monodrama, the percussionist Gert Sørensen, who had, already at that time, acquired great knowledge and expertise on the subject. Percussion, generally, takes up a lot of space,, and even though I always go to great lengths to ensure that the individual percussionist has enough time to switch between the different instruments, Gert and I agreed, based on the enormous array of percussion in GONG, that he should sample, not all, but a portion of the percussion, and thus get them all placed on one keyboard, a so-called sampler.

The digital piano that I had bought naturally contained a piano program, but also one for strings and harpsichord. I found that the different programs could be combined, such that the piano could be “paired” with the strings and so forth. In the end I didn´t use it, but quickly realized that if I held the whole hand down on all the keys, black and white, all the way at the bottom (a so-called cluster) in the deepest octave, the sampled strings gave a terrific, sucking sound, a bit like a gas leak. I use that in a couple of the very last bars of GONG. Likewise, toward the end, I prescribe: harpsichord: the music here is placed a full two octaves below what a normal acoustic harpsichord has. The “new” artificial sound is quite striking. Does not sound like anything else.

Neither does GONG, if I may say so myself. It is also the wildest I have ever written. The sun is a nuclear reactor that has now burned for a good 4567 million years, and, as my old friend and schoolmate, the astrophysicist Bo Reipurth, tells me, will continue for another 5 billion years before it swells up and becomes a “red giant,” which will swallow the planets Mercury, Venus, and Earth (Mars will probably get away with “only” having “its rump singed”), to then shrink and die out. To describe that in music cannot be done, one would think, but that is precisely what I set out to do, without shame: 10 billion years cut down to 18 minutes. Although our sun is “only” an ordinary medium-sized star, its energy is unfathomable. The surface temperature is 6000 degrees Celsius, and it hurls out so-called prominences, magnetically over-heated gas at a speed of 600–1000, perhaps more, kilometers per second. It sings and dances with energy. And the designation Dancing is precisely what I have given to the section where the piece really begins.

Dancing, okay, but the music is totally chaotic.

It explodes, pulses, pumps, bangs, screams, howls, rocks and roars in one unbroken rampage, with a decibel level bordering the permissible (more about that later). The music is really on the edge of the bearable, it sounds like chaos, and is so, but only on one level: the manner in which

I composed it. The graph paper remained in the drawer this time, likewise the permutation principle was put on ice. I realized that if I were to describe on earth what nuclear wildness goes on inside a star 150 million kilometers away, I had to set aside the civilized measurements and instead surrender myself to the totally unpredictable, let chance rule.

In my work for alto soloist and orchestra, The City in the Sea (after E. A. Poe), composed immediately before I started on GONG, I had built up what I called a chord bank, 41 towering chords, spanning over the entire keyboard, so to speak, and now, when GONG stood on the agenda, I once again grabbed hold of the chord bank and… cut it into bits and pieces! And put the pieces together again, according to the tombola principle, each “clipping” was pulled up by me, blindfolded, metaphorically speaking. Each piece I fished up from a cardboard box I had on the desk next to me, had to be used, no going back, nothing like… “no, I’ll try once more.” So the whole pulsing explosion in the orchestra is the result of total chance. But a chance that is kept on a tight leash rhythmically. The meter is three half-notes in each bar, three beats, where the individual beat is subdivided into four eighth-notes. That makes it relatively simple both to play (the individual parts are not difficult in themselves) and to conduct. And not a living soul will know that the whole thing is put together by a “blindfolded” composer. It “just” sounds extremely violent, and it continues without letting up, until I put the madness on pause for a couple of minutes by letting a single chord stand alone and simmer and sizzle, only to unleash all hell again.

It also became a kind of hell for the poor musicians in the RSO, with whom I, until then, had had a really good relationship (and still have), but GONG put the “friendship” to a test. After the first run-through, the principal oboist came over to me and said, “…what is this now, Poul? This isn’t like you.” There was no talk of revolt as such in the orchestra, but it was an ordeal for them to play it. They had never before experienced anything like it. The piece was, as earlier mentioned, supposed to have been included in their upcoming USA tour, but they replaced GONG with Thus Saw St. John. It may also have played a part, that the colossal percussion array in GONG was too extensive and too cumbersome to take on tour. And even though “Thus saw..” is not for the squeamish either, there is still a long way to the ear-splitting rage of GONG.

After the premiere in the old Radio House on Rosenørns Allé, the composer Bent Lorentzen came over to me and said, with a big smile: “…who do you think you are,, coming here with such a radical work?” Even the 83-year-old Vagn Holmboe, whose Trombone Concerto was premiered on the same occasion, thanked me with a smile, but I do think he was somewhat

shocked. Although GONG was not loved by the musicians, they were—and are—professionals, so the subsequent studio recording (together with the Symphony, Tundra and Saaledes saae Johannes) for the British label Chandos went on to become a huge success, not least because of the unique conductor Leif Segerstam, who certainly did not let himself be frightened by the violence in GONG. On the contrary, he led the battle(literally) with undisturbed calm and overview. The CD (which also offers the First Symphony, Tundra and Thus Saw St. John was released in 1993 and received almost a whole page review in The Independent, where the culture desk had hatched the idea of letting two critics come up with their verdict of the same CD, although independently of each other. Both were crazy about, especially, GONG… but at the same time disquieted, for it was indeed one savge affair.